NEW! The Gist (FREE) | E-BOOKS |

The Gist of Kurukshetra Magazine: April 2013

The Gist of Kurukshetra Magazine: April 2013

Contents

- New Areas in Rural Employment

- Need to Strengthen Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

- Need to Strengthen Vocational Institutes in Rural Areas

- Demand Registration

- Asset Quality

- Concluding Remarks

- Lack of Social Security

- Need for New Plan Strategy

- MSME Sector through Cluster Development

- District Rural Industries Project

- Maharatna Status to BHEL and GAIL

NEW AREAS IN RURAL EMPLOYMENT

In India, 69 per cent of our population lives in the rural areas and majority of people in rural areas depend on agriculture for their livelihood. But, according to the data of the National Sample Survey (NSS), the growth rate of employment has declined from 69 to 55 per cent in agriculture. Consequently, the share of agriculture and allied sectors in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) has been reduced to 14 per cent. Unemployment which was 7.2 per cent in the year 2000, increased to 8.1 per cent in 2010 in comparison to urban unemployment rate which increased from 7.7 to 7.9 per cent during the same period. The higher unemployment and low income per capita in the rural areas result in low purchasing power of the rural people and it also affects the spending on important sectors like health and education. Overall, the youth in the rural areas feel disillusioned to continue with this profession. As per the data of NSS, 40 per cent of people in the rural areas want to leave agriculture as a profession if they get better option of occupation. This is certainly is not a good sign for food security of our country which is of paramount importance and backbone for our all development initiatives. The aspirations of the people are same in the rural and urban areas which result to migration from rural to urban areas in the hope of better living standards. In 2009-10, according to the NSS survey, average monthly per capita expenditure stood at Rs 1,053.64 in rural areas and Rs 1,984.46 in urban India, there remained a huge gap between the incomes of the top and bottom segments of the population. It also found that food items accounted for the bulk of the expenditure, with the share of food in total household spending at 57 per cent and 44 per cent in rural and urban areas, respectively. Somehow, conomic reforms have bypassed agriculture and rural development prospects. Thus, rural economy and agricultural sector has shown a very low rate of growth.

NEED TO MAKE FARMING MORE PROFITABLE

The Scheme of Agri-Clinic and Agri-Business Centres was launched in 2002 as a follow-up of Finance Minister’s budget speech for 2001. The objective of the scheme is to provide fee-based extension and other services to the farming community and also to create self-employment opportunities for agriculture graduates. The agriculture graduates are provided training in agribusiness development for two months in over 67 institutions in public/private sector located throughout the country and coordinated by National Institute of Agriculture Extension Management (MANAGE). These institutions also provide hand holding support to the trained graduates for a period of one year. The entire cost of training and hand holding is being borne by the Government of India. Trained graduates are expected to set up Agri-Clinic and Agri-Business Centres with the help of bank finance. The scheme is being implemented with the help of Small Farmers Agri-Business Consortium (SFAC), MANAGE and National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD). The training is open for graduates in agriculture and any subject allied to agriculture like horticulture, sericulture, veterinary sciences, forestry, dairy, poultry farming, fisheries, etc. Now the facility has been extended to the youth with agriculture diploma of one year after 10+2 examination.

MANAGE will publish advertisement for inviting applications for training in leading newspapers of national and regional importance. After the training, these graduates and diploma holders can start different agri-businesses and loan up to Rs. 20 lakh is provided by the NABARD and other nationalized banks out of which around 40 per cent is financial assistance.

NEED TO STRENGTHEN MAHATMA GANDHI NATIONAL RURAL EMPLOYMENT GUARANTEE ACT

The MGNREGA is perhaps the largest and most ambitious social security and public works programme in the world. This scheme has certainly a boon for the rural people in strengthening their economic conditions. Since its inception in 2006, around Rs 1,10,000 crore has gone directly as wage payment to rural households and 1200 crore persondays of employment has been generated. On an average, 5 crore households have been provided employment every year since 2008. The notified wage today varies from a minimum of Rs. 122 in Bihar, Jharkhand to Rs. 191 in Haryana. There is need to increase the days of employment from 100 days in a year to at least 150 days. In addition, more farming activities should be brought in its ambit to benefit the farmers. This will prove synergistic to agriculture growth also. Keeping in view the success of this programme, United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has signed a memorandum with the Indian Government to support this programme during the Twelfth Five Year Plan (2012-2017).

Training Opportunities Seff- Employment

Opportunities of self employment are the best alternative to augment the existing agriculture income of the people in the rural areas. Central Government is taking various initiatives to create such opportunities. The Ministry of Rural Development has established Rural Self-Employment Training Institutes (RESTI) in all the rural districts of the country to create skilled manpower for making people able for such jobs.

These institutes are supported, managed and run by the public/private sector banks. These institutes are providing free, unique and intensive short-term residential training modules to the rural youth. So far, more than 190 RSETls have been established in different The training programmes under RSETls are entirely free of cost. On an average each RSETI offers around 30-40 skill development programmes on different areas in a year. All the programmes are of short duration ranging preferably from 1 to 6 weeks. States of the country with active participation of 35 public/private banks, and these institutes have trained more than 1.5 lakh rural youth on various trades. These training modules for the self employment are related to different fields. In agriculture and allied sectors, focus is on activities like Dairy, Poultry, Apiculture, Horticulture, Sericulture, Mushroom cultivation, floriculture, fisheries etc.

In Product Development Programmes, training is focused on Dress designing for men and women, Rexine utility Articles, Agarbatti manufacturing, Football making, Bags, Bakery Products, Leaf Cup making, Recycled paper manufacturing etc. In Process related Programmes, people are trained in Two Wheeler repairs, Radio / TV repairs, Motor rewinding, electrical transformer repairs, irrigation pump-set repairs, tractor and power tiller repairs, cell phone repairs, Beautician Course, Photography & Videography, Screen Printing, Photo Lamination, Domestic Electrical appliances repair, Computer Hardware and DTP. In addition, training is also given in sectors like leather, construction, hospitality and any other sector depending on local requirements. One important feature is that the RSETI conducts only demand driven and need based training programme with an intention to provide self-employment to rural youth. Training programmes are decided by the local RESETI as per the local resource situation and potential demand for the products and services. Soft skill training shall be an integral part in all the training programmes.

Credit linkage of the trainees is one of the important

aspects of RSETI training programme. After completion of the training programme,

institute sends the list of the candidates to the bank branches and co-ordinate

with them for extending financial assistance to the trainees for taking up

entrepreneurial activities. The institute also involves successful ex-trainees

with bank branches to make credit available to the trainees.

Technology is making huge strides in the recent years. Thus, it becomes a

necessity for the entrepreneurs to hone their skills to match up with the latest

cutting edge technologies. Realizing this importance, RSETls conduct various

skill upgradation programmes for undertaking micro-enterprise and to enable the

existing entrepreneurs to compete in this ever-developing global market due to

technological change. These programmes are budgeted for and conducted as

refresher programmes for not more than week duration.

Need to Strengthen Vocational Institutes in Rural Areas

Skill development has been the major focus of the Central Government to increase the employment opportunities among the youth and also to cater the demand of skilled labour force in the industry. But, there is need to create such facilities in rural areas to augment the income of the rural people. To give impetus for the skill development, Prime Minister’s National Council on Skill Development was constituted in 2008 to pave the way for coordinated Action for Skill Development. National Skill Development Corporation was formed and its aim is to promote skill development by catalyzing creation of large, quality, for profit vocational institutions. The National Skill Development Council under the Chairmanship of the Prime Minister has formulated a major scheme for skill development in which 8 crore people will be trained in the next 5 years. In this ambitious scheme, youth will be skilled with short duration training courses of 6 weeks to 6 months. The Central Government is considering the establishment of a National Skill Development Authority so that skill development programmes all over the country can be implemented in a coordinated manner. A Nation-wide scheme of “Sub-mission on Polytechnics” has also been launched. Under this scheme new polytechnics will be set up in every district which is not having the same with the Central funding and over 700 will be set up through Public Private Partnership (PPP) and Private funding. The existing Government Polytechnics will be incentivized to modernize in PPP Mode.

Rural Wage Gurantee Implementation Challenges

To achieve growth with equity and social justice, the Government of India (Gol) has been implementing specific poverty removal programmes since the Fifth Five Year Plan (1974-79). This direct attack on poverty was spear-headed by a two-pronged strategy of wage and self-employment programmes. Poverty alleviation and employment-generation programmes have been re-structured and re-designed from time to time to make them more effective. Gol’s most recent initiative under the wage employment programmes is the launch of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) on February 2, 2006.

Wage Guarantee and Livelihoods

The main object of MGNREGA is to provide for the enhancement of livelihood security of the rural households by ensuring a legal right of at least 100 days of unskilled wage employment to willing adult members. As a safety net for the poor, this Act aims at creating a demand-driven village infrastructure, including durable assets, to increase the opportunities for sustained employment. Thus, MGNREGA supplements and broadens rural occupational choices besides regenerating natural resources.

MGNREGA was initially implemented in 200 districts. During the FY 2006-07 it was extended to 330 districts and to all the districts (615) during the FY 2007-08. The Act is now being implemented in 626 districts. Physical performance of the programme indicates that the wage employment generated per household is much below the minimum of 100 person-days. While at the national level, the average annual person-day employment generation during 2006-07 to 2008-09 ranged between 42 (2007-08) and 48 (2008-09) person-days, during 2009-10 to 2011-12, the average employment ranged between 54 (2009-10) and 43 (2011-12) person-days. State-wise employment generated data indicates that during 2009-10 there were 16 States which experienced employment generation below the national average of 54 person-days. During 2010-11 and 2011-12, there were 14 and 12 States which witnessed employment generation lower than the national average of 47 and 43 person-days, respectively. The MGNREG Act 2005 vested the responsibility of the implementation of the programme with the States. Although MGNREGA focuses on planning for productive absorption of under-employment and surplus labour force in rural areas by providing up to 100 days of direct supplementary wage employment to the rural households, the decline in person-day employment generation has become a matter of concern, discussion and debate. A brief review of select statistics on the progress of MGNREGA since 2008-09 is in Table 1.

It is against this backdrop that this paper attempts to analyze some of the important implementation issues and challenges under MGNREGA. Let us discuss some of the important issues and challenges which require immediate attention to achieve the intended objectives of MGNREGA.

Demand Registration

Demand for works under MGNREGA are generally accepted by Gram Rozgar Sewaks (GRS) functioning at the GP / Village level on the basis of applications received from the Registered Households. The process of demand registration is a bit cumbersome for the illiterate and unskilled MGNREGA workers. Often inadequate staff strength at the village/GP level limits the demand registration process and restricts labour demand. While improvement of grass-root level implementation staff is the need of the hour, the States should take help of Interactive Voice Response (IVR) technology not only for registering work demand but also for receipt, examination and redressal of grievances related to registration of demand under MGNREGA.

Timely Payment of Wages

There is a positive and direct correlation between timely payment of wages and registration of labour demand. The lower than expected labour demand in various States under MGNREGA is due to inordinate delays in wage payments. Further, timely wage payments depend largely on apt and well-timed measurements of works.

The States should adhere to a fixed (14 or 15 day) schedule for payment of wages, appointment of business correspondents where the banking outreach is either negligible or absent and rolling out of e-based innovative systems viz. (a) Electronic Muster Management System (e-MMS) (b) Electronic Fund management System (e-FMS). While e-MMS will ensure complete transparency in the implementation of MGNREGA by capturing real time transactions from the worksite and uploading these to the Ministry’s Website on a day to day basis, e-FMS will bring in a real time transactionbased e-Governance solution by addressing the problem of delays in payment of wages and real time capturing of the MGNREGA transactions (e-Muster Rolls and e-Measurement).

Staff Strength and Capacity Issues

MGNREGA, due to its country-wide outreach and manifold legal and procedural requirements, calls for a mission mode approach in its implementation. The implementing States need to constitute State level MGNREGA Missions supported by a dedicated State level management team.

The State Mission should extend support services to the nodal .departrnent on technical and administrative issues and guide the districts and panchayat institutions in the effective implementation of the programme. The Mission should also have adequate operational flexibility and a facilitative Human Resource (HR) policy to recruit and retain a team of committed experts. Professional team at the state level should consist of specialists in important thematic areas viz. grass-root planning, rights and entitlements, works and their execution, timely wage payment, management of records (technical, administrative and financial), information communication technology (ICT), training and capacity building, information education and communication (IEC), management information system (MIS) and monitoring and evaluation (M&E), social audit and grievance redressal. On similar lines, district and sub-district agencies should plan for constituting a separate expert cell to implement MGNREGA in a mission mode.

Planning Public Works

MGNREGA envisages fixing priorities of activities while providing a basic employment guarantee in rural areas. It is mandatory under MGNREGA to formulate action plans and perspective plans prior to implementation. As per Schedule-I of MGNREGA, the focus of the Act should be on activities related to water conservation, water harvesting, flood and drought proofing, irrigation, land development and rural road connectivity. During field visits, it is often experienced that farm ponds were being dug under MGNREGA in several places without having a detailed plan of action. Beneficiaries and the executing government officials seem to have no satisfactory answer on the usability of such ponds in dry seasons. Neither such ponds recharge the ground water aquifer, nor is adequate care taken to identify individual/community needs for such type of intervention. It is, thus, imperative to have a rigorous cost-benefit analysis of any public works initiative. To have a complete impact of the MGNREGA initiative, an active involvement of national and State level experts like engineers, architects and planners is a must in identifying land masses needing proper management, arriving at topographic specificities, effective flood/drought proofing methods and disaster management measures. Since there is an essential need for an integrated management of flood d drought forecasting services in India, providing an agency of experts in this field under the Act could ensure sustainability of activities and optimization of the resource utilisation at the grass-root level.

The works taken up under MGNREGA should shift from taking up large ponds, canals, open wells, etc. to an integrated natural resource management mode. Planned and systematic development of land and careful use of rainwater, following watershed principles to sustainably enhance farm productivity and incomes of the poor, should become the central focus of MGNREGA. Works should be taken up on the basis of multi-year plans drawn at the level of natural village or hamlet through a participative process. Such plans should have a built-in provision for convergence of other schemes, such as Rastriya Krishi Vikas Yojana (RKVY)/ Rainfed Areas Development Programme (RADP), National Horticulture Mission (NHM) etc. to enhance productivity and income.

Asset Quality

Ensuring, quality assets through, MGNREGA activities has really been a challenge for the implementing States. Though the programme is meant for unskilled labourers in the rural areas, yet, proper planning and technical appraisal of the activities would ensure quality and durable rural infrastructure. The States, thus, need to create a separate asset quality and monitoring cell to guide the project implementing partners to ensure productivity and sustainability of assets created under MGNREGA. State Quality Monitors should be appointed to check the quality of MGNREGA assets and suggest work-wise improvements. Assessment/inspection reports on quality of assets and their utility should be uploaded onto the website so as to disseminate the findings/recommendations of the quality monitors.

Convergence Effort

Land and watershed development, water conservation, flood and drought proofing and newly notified agri-related activities promise to contribute greatly to the economic and ecological development of rural areas, particularly in drought-prone and dry land areas. However, before the extension of MGNREGA to the hitherto untreated regions, efforts should be made to determine the priorities of permissible activities designed for creating durable community assets. Thus, the objective of asset creation should take into account local needs and priorities. Further, construction of assets like irrigation, flood protection, water conservation etc., should tap the funds budgeted by sectoral departments of the States concerned. Though the Gol has initiated its effort in converging MGNREGA with other ongoing programmes of Ministry of Rural Development, Ministry of Agriculture, Ministry of Water Resources, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Department of Land resources, there is an emerging need to design and implement policy directives on convergence at the district/block/village level with the all-round co-operation of the district/Block level sectoral line departments.

People’s Participation

MGNREGA envisages an active participation of the three-tier self-government. The: implementing mechanism under MGNREGA advocates free participation to democratically discuss local issues and problems, identify the ways and means for their resolution and demand such facilities which could improve the quality of life of the village community at large. This objective will be achieved only when the Panchayat functionaries in consultation with the local people, review the existing infrastructure and the need for their expansion under the Act for making the MGNREGA activities demand-driven. Preparation of action plan/ perspective plan under the Act requires energetic involvement of the various levels of self-governments.

Social Audit:

As per the notified Mahatma Gandhi NREG Audit of Schemes Rules, 2011, each Gram Panchayat has to conduct at least one social audit every six months. To facilitate the Social Audit process, each State needs to set up an independent Organisation, preferably, an Autonomous Society to spearhead the Social Audit process Of MGNREGS in the State.

Proactive Disclosure of Information:

To facilitate Social Audit and to enhance transparency, all information about MGNREG scheme including the families benefitted, estimate of works, payments made, etc. should be displayed in all hamlets of GPs by way of wall-paintings and notice boards. A detailed Report on MGNREG schemes giving details of employment provided, households benefited, wages paid, works undertaken, etc. may be prepared and placed in the Gram Sabha by the GP in the first month of every financial year. This kind of proactive disclosure of information to the people will increase transparency and accountability in MGNREGA implementation.

Concluding Remarks

The concepts of the Act are novel and innovative though the

Act continues to suffer from age-old operational and functional rigidities, like

its predecessors. The performance of the MGNREGA has been severely skewed across

States. The average person-days employment per household has not improved

between 2008-09 and 2011-12. While the problem of delay in the payment of wages

to the MGNREGA workers under the Act needs to be urgently addressed, the demand

registration processes under the programme at the GP/village level need a

complete overhaul to capture latent labour demand in the rural areas.

MGNREGA assures generation of employment opportunity in the rural areas by

absorbing casual labourers in the rural labour market. Resolution of important

programmatic and institutional issues viz. quality of assets created under

MGNREGA, social audit, planning and staffing are the need of the hour. Further,

proactive disclosure of programme information and dissemination of core

provisions of the Act through print, electronic media and innovative street

plays would help not only in ensuring transparency in implementation but also in

generating awareness and building capabilities among the rural employable poor

households.

Plight of Women Domestic Workers in India

In the emerging global economic order, characterized by global cities, new forms of division of labour and change in demographic composition, paid domestic work, mainly supplied by the poorer families, in particular women, tends to substitute unpaid production activities and services within a family such as cooking, cleaning utensils; washing clothes, caring children and old aged and so on. This makes domestic work as a pivotal occupation in determining the linkage between family and the dynamics of open economy. Across the globe, although this linkage is quite vivid, reflected in ever expanding demand from families for domestic worker’s service, provision of entitlements to this occupational category varies across countries.

The plight of domestic workers in India is heart-rending. They are an important category that tends to be de jure or de facto unprotected No one knows how many women work in domestic service in India. Official figures suggest 5 million. One study assesses the number at 40 million and the International Labour Office reckons it is somewhere between 20 and 80 million. Some observers believe even this higher limit is an underestimate. if true, this would indicate that up to ten per cent of the female population over the age of 12 are employed in domestic service. There has never been a systematic count, although it is the second largest employer of women after agricultural labour. Invisible, unregulated, poorly paid, even a definition of domestic servant proves elusive and contradictory. Most of this subjugated workforce, of an estimated 90 million domestic workers in the country, comes from impoverished regions in states like Jharkhand, West Bengal and Chhattisgarh. It’s no surprise that a substantial number of them are trafficked into big cities to spruce up urban homes, smoothen out the harried lives of city-dwellers.

West Bengal alone reported as many as 8,000 missing girls in 2010 and 2011. Hapless girls from the tribal regions are especially in demand. They are simple and innocent and, crucially, without a support structure. So abuse is rarely reported. Often the parents have no idea where the girls have been taken by agencies and, being illiterate, they are open to all sorts of exploitation. A survey in Mumbai two years back found nearly 60,000 girls between 5-14 employed as domestic workers. Now there’s a common rationalisation, more so among this very same middle class, that at least these kids are being fed and clothed, that they are lucky to not find themselves in a brothel. But that’s no guarantee that they won’t end up being sexually abused by their employers. 1.26 mn children work as domestic helps, 86% are girls and 25% of them under 14-the minimum age prescribed in anti-child labour laws.

Unpaid Work

In Indian context, the enormity of informal work is quite a discernible phenomenon; approximately 93 per cent of workforce is engaged in paid work in farming and non farming activities, for which they are not entitled to any of social security benefits. Moreover, these workers tend to receive relatively lower wages than formal workers get. Going by patterns generated from employment data published by National Sample Survey Organization, Government of India, persons with more years of schooling (close to ten years), appear to have higher chances of getting formal work which makes them eligible for entitlements like social security, while persons with less years of schooling may end up in lower echelons of labour market, earning lower wages and that too without social security.

Quite importantly, the dichotomy of formal-informal work coexists with glaring low labour force participation of women. Although across age groups, female work participation rate is much lower than male work participation rates, in some occupations female far exceeds male. For instance, this is quite evident for the occupational category ‘domestic work’. As it appears from data, domestic work seems to be a feminine occupation for which significant part of demand for labour comes from the urban sector. Domestic work seems to be the destiny of significantly huge number of women workers in India who seek employment opportunities in urban sector, often rendering an invisible workforce who are not paid well, and deprived of rights to ensure decency in work.Reflecting on indecent working and living condition of women domestic workers, National Commission for Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector views: “Working in the unregulated domain of a private home, mostly without the protection of national labour legislation, allows for female domestic workers to be maltreated by their employers with impunity. Women are often subjected to long working hours and excessively arduous tasks. They may be strictly confined to their places of work. The domestic workforce is excluded from labour laws that look after important employment-related issues such as conditions of work, wages, social security, provident funds, old age pensions, and maternity leave.”

It is important to note that there were active initiatives to mobilize domestic workers in India, paving way for lobbying for rights such as minimum wage. In 1959, New Delhi based All India Domestic Workers Union (AIDWU) called for a one-day solidarity strike which received a thumping response from domestic workers. Interestingly, this initiative attracted legislators’ attention; two bills-on minimum wages and the timely payment of wages, maximum working hours, weekly rest and annual leave periods, as well as the establishment of a servant’s registry to be maintained by the local police, in deference to employers- were introduced. However, these bills were withdrawn later. Further, the development of organizing workers had a major setback when Supreme Court of India ruled that isolated workers cannot form organized labour, implying that occupational categories like domestic work is not entitled to the status of organized labour (ILO, 2010a). In fact, discrete outcomes of this nature punctured the organic growth in organizing domestic workers, one of the reasons why domestic work remains as an occupation not entitled to rights such as minimum wage and social security.

However, ongoing legislative initiatives such as Unorganized Sector Workers’ Social Security Bill, which covers a broad range of security schemes for workers in the informal sector, including domestic workers, is a major break-through with a potential for desirable improvements in working and living condition of domestic workers. While pervasive deficits in working and living conditions remain scary, inducing voices of dissent against lack of volition from the state to assure decent work for domestic workers, India lags behind other nations in extending rights to domestic workers.

Lack of Scoial Security

As shown in ILO (2010a), India is yet to provide core entitlements for decent work like maternity benefit. On the other hand, 26 nations, including developed and developing countries provide 12-14 weeks of maternity leave for domestic workers. Moreover, national minimum wage act 1948 excludes domestic workers from its purview. However, states, members of federal union, may fix minimum wage for domestic workers within their territory. Another important deficit is lack of social security to domestic workers in India while there have been noteworthy initiatives by other countries to provide different types of social security to domestic workers - occupational safety and health, workers’ compensation for employment injuries, general health care, pension and unemployment insurance. In fact, for women engaged in domestic work, in particular in urban India, even generating subsistence level income entails a complex process of scheduling of activities since they tend to work with multiple employers, who prefer flexible forms of labour contracts like part time engagement of domestic workers. Unfortunately, these workers, incurring the risk of working in indecent conditions, are enmeshed in a system with excess supply of workers; they tend to offer services to relatively well-off households, who are likely to have much better availability of rights and entitlements.

Strategies for Employment Generation in Rural India–A Critical Evaluation

One of the major problems facing our country today is the continued migration of people from rural to urban areas which is essentially a reflection of the lack of opportunities in the villages. Unemployment and poverty continues to plague the Indian economy despite almost half a country of planned development, the magnitude as well as the percentage of unemployment and under employment has been on the rise. However, the achievement in the field of employment generation is far below the target.

World Unemployment Scenario According to growing unemployment scenario the unemployment is rapidly increasing both in Asian and European counties. In Asia unemployment percentage is increasing by 2 to 5 percent per annum. Among the Asian countries the unemployment growth rate is gradually increasing due to rapid growth of population, China with a population of 134 crore could provide employment to 96 percent of its population, but India with a population of 124 crores hardly provides employment to less than 30 percent of its total population. The growing unemployment scenario in the world reveals that in China the unemployment ratio is 4.1 percent, Bangladesh 4.5 percent, Russia 502, Spain 18.2, Germany 13.3, Italy 13.6, Japan 5.6, Pakistan 5.6 percent, USA 7.7, England 7.8 and in India the unemployment growth ratio is 9.5 percent. This reveals that the situation in India is worst than that of Bangladesh and Pakistan. Indian economists observed that India has to learn a lesson from China and Japan to improve employment ratio.

Nss Report in India (2011)

According to National Sample Survey Report 2011, about 2.5 crore vacancies are yet to be filled up by the central and state governments in our country. As per the National Employment Survey Report (20ll), the unemployment ratio in India is vastly growing without any solution. The report reveals that out of 100 populations the unemployment ratio in Haryana is 37 percent, Tamil Nadu 39 percent, Karnataka 41 percent, Punjab 50 percent, Gujarat 38 percent, Kerala 58 percent while in Andhra Pradesh ratio is 67 percent. According to the graph it is a paradoxical truth that due to growing population the unemployment growth ratio is also growing with a rapid speed. In the year 1961 the growth ratio was 3.2 percent in 19714.6 percent, 1981 it was 5.2 percent while in 1991 the growth was 6.4 percent, in 2001- 7.8 and as per the 2011 census the ratio has increased to 9.4 percent in India.

Stete Wise Current Population and Unemployment Ratio - 2012

The table given below indicates the state wise growing population and unemployment growth ratio in our country.

Source: National Unemployment Growth Ratio - 2012

The Table given above would indicate state wise unemployment growth ratio. Some states like Bihar has gained nothing either from rural employment or from the urban employment. A few states like Rajasthan, Punjab and Haryana have benefitted in reality from high employment both in rural and urban areas. Few states likes Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh which constitute 52.2 percent of the total population account for 50 percent of the total unemployment. While Maharashtra, Rajasthan, Karnataka and Gujarat which constitute 38.60 percent of the total population account for 32 percent of the total unemployment. Few state like Orissa, Punjab, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh and Assam which constitute 20.85 percent of the total population, account for 13 percent of the unemployment. These sates are considered to be better off in the field of unemployment generation. Thus it is policies need to be implemented policies need to be implemented with urgency to generate rural employment.

Growth Rate of Rural Employment

According to NSS data between 1972 to 2012 the growth of rural employment has increased by 2 percent per 9224, but suddenly reduced to 1.75 in the year 1992-93. While the employment percentage has increased by 2.02 between 1997-2002 and 3.2 percent in 2007, while the employment ratio reduced to 2.08 percent in 2012. But the situation is totally different in urban region. The employment ratio increased from 4.31 (in 1972-78) to 5.08 percent in 2012.

The main objective of Employment Guarantee Scheme is to sustain household welfare in the short run through providing employment and contribute to the development of rural economy in the long run through strengthening the necessary infrastructure. Apart from Maharashtra, few other states also attempted employment guarantee scheme with in their limited resources. Some of them were Land Army Corporation (LAC) in Karnataka (1974) State Rural Employment Programme in Tripura (1981) Village Development Council in Nagaland (1978) etc.

Employment Generation Programmes

The Government of India was committed to formulate various plan policies on rural employment during the successive Five Year Plans. However, the architects of Fourth Five Year Plan realized the need for balancing the regional imbalances in the field of rural employment and landless agriculture labourers. Thus came into existence the Small Farmers Development Programme (SFDP) to provide better employment opportunities to eradicate poverty, Drought Prone Area Programme (DPAP), Minimum Needs Programme (MNP), etc.

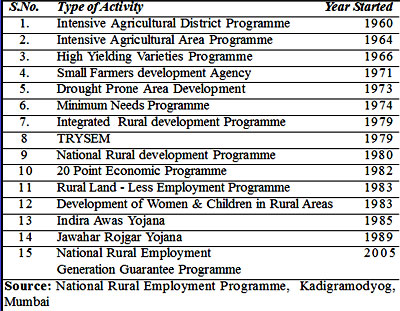

Source: National Rural Employment Programme, Kadigramodyog, Mumbai

The five year plans however laid emphasis on a large scale on a Rural Manpower Programme (RMP) in the end of 1960-61 in 32 community development blocks on a pilot basis for utilizing the rural manpower to provide employment for 100 days to at least 2.5 million by the end of the Third Five Year Plan. Although the scheme achieved the immediate objective of providing employment opportunities, the benefits of both in terms of direct employment and assets creation are found to be too widely scattered.

A pilot initiative Rural Employment Programme (REP) was started in November, 1972 in 18 selected blocks for a three year period, to provide additional employment opportunities to unskilled labourers. The project completed its full term of three years and generated 18.1 million man days of employment. Apart from this the Drought Prone Area Programme (DPAP) one of the panned attempts in this direction covering 74 districts in the country. A critical outlay of Rs. 187 crores was provided in the fifth plan against 100 crores in the fourth plan.

During April, 1977 Food for Work Programme (FWP) was started as a non plan scheme to augment the funds of state government by utilizing available stocks of food grains. The basic objective of the programme was to generate additional gainful employment for unemployed persons in the rural areas and to improve their income. As such a total employment of 979.32 million man days was generated during 1977-80. Thus this scheme became popular in rural areas and was neglected as a major instrument in generating rural employment while the sixth plan launched a nationwide National Rural Development Programme designed to provide gainful employment in rural areas to the extent of 300-400 million man days per annum to provide durable community assets. In addition on 15th August, 1983 a new employment provision programme called RLGEP was launched with a view for providing guarantee of employment to at least one member of every landless household up to 100 days in a year by creating the infrastructure of the rural economy. This programme was implemented through District Rural Development Agency (DRDA) setup allover the country. The sixth plan devised a new strategy called Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) basically an antipoverty programme. The core of IRDP is therefore to provide poor families with income generating assets to enable them to generate incremental surplus to cross the poverty line. The above two programmes merged to give birth to a new programme called Jawahar Rojgar Yojana (JRY). The basic rationale for the lack of employment opportunities in the countryside is one of the reasons for the rural poverty. The IRDP target initially was to cover 15 million beneficiari s at the rate of 600 per block per year with a view to diversifying the occupational structure.

Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Generation Act

The success of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme is said to be one of the big resources that UPA Government returned to power in May 2009. This land mark scheme implemented in 2006 guarantee 100 days of unskilled work to an adult family from rural household during a financial year.

The Act was introduced in 200 districts in the first share with effect from 2006 and additional 1135 districts covered un the year 2007-08.

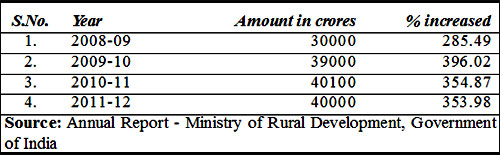

The following table shows central financial outlays for MGNREGA from 2008 to 2012.

Source: Annual Report - Ministry of Rural Development, Government of India

The MGNREGA makes it mandatory for job keepers to have a job card for which the rural people have to apply to the Panchayat. In order to facilitate the rural house hold the Government of India has issued Job Cards to the rural people. Today by the end of December, 2012 about 28 crore job cards were issued to the rural hosehold families to generate employment.

Need for New Plan Strategy

The problem of unemployment in rural India can be eradicated only by increasing productivity of dry land agriculture. In this context we need a constitution of greater emphasis on research and development. Another key element is the strategy for effectively tackling the problems of rural unemployment in accelerating the tempo of rural industrialization. Rapid growth in the non-agricultural sectors of the planned development has completely failed to make any noticeable impact on the work force. Development of infrastructural and marketing arrangements for the growth of non-agricultural activities in rural areas is the need of the hour. Greater flexibility in special employment programmes and their integration with sectoral development to ensure their contribution to growth and sustainable employment would help in generating employment opportunities in rural India. The experts are of the opinion that an expanded programme of development and utilization of waste land for crop cultivation and forestry, would help in generating regular employment to the rural masses.

Conclusion

The planning commission report reveals that the demand labour curve is downward sloping to the right. There is a great need to implement land reforms policy to create rural employment strategy with respect to productivity of dry land farming. The wage employment programmes in India started from the experimentation of pilot projects are now towards a scenario moving which generates employment.

Public Participation and Accountability in MGNREGA

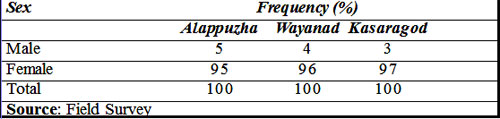

One of the striking features of the scheme as evidenced in the data available is the high levels of women’s participation in the works. In all the six Panchayats under study from the three districts women were found more involved in the scheme. Some of the highlights of the sample are as follows:

In our survey ninety five percent beneficiaries of Alappuzha, ninety six percent in Wayanad and ninety seven percent in Kasaragod turned out to be women. Beneficiaries in the age-group of 20-50 accounted for the largest group-eighty one percent in Alappuzha, seventy four percent in Wayanad and sixty five percent in Kasaragod. For including the Scheduled Tribes in our study we selected 100 respondents belonging to tribal communities in Wayanad. The respondents included Paniyas, Adiyas and Kurichyas. For including the Scheduled Castes we selected 100 respondents belonging to Scheduled Castes communities from Kasaragod. The Alappuzha sample consisted of seven percent Scheduled Castes, thirty five percent from Other Backward Castes and fifty eight percent from the general category. The respondents were mostly married. In Alappuzha of the total 100 samples, ninety nine respondents were married. Similar is the case of Wayanad (98 percent) and Kasaragod (99 Percent). All the respondents from Alappuzha, ninety eight percent from Wayanad and ninety nine percent from Kasaragod belonged to BPL families.

Women’s Participation in MGNREGP

The MGNREGA’S potential in empowering women by providing them

work opportunities has been commented on by many scholars. The reasons that

contribute to women’s participation are many. Women from all the three districts

considered the work as a high social status job similar to a white collar job

under the Central Government. In the Kerala situation, an unskilled male

labourer working for a day can earn around Rs. 350/-.

But through MGNREGP one person can get only a much lower amount per day. So

mostly men prefer to go for outside work. Women on the other hand are happy to

work at low wages. This results in their greater involvement in these works.

Infact, all the women respondents from Alappuzha and Kasargod and ninety eight

percent out of the women respondents from Wayanad said that they are happy with

this scheme. They expressed the fond hope that this scheme will continue in full

earnest. Indian society being a patriarchal one does not often welcome or

appropriate women’s voices or even her presence in decision making processes and

forums. One of the striking features of MGNREGP as evidenced in the data

available is the high levels of women’s participation in the works. The range is

given in the table below.

Table 3 Male/Female participation (in %)

Source: Field Survey

The very fact that 95 percent or more of the workers from all the three districts under study are women has imparted a positive gender dimension. The participation rate of women in MGNREGP clearly shows that economic support provided by the women labourers in supporting the family is welcomed by the Kerala society. But a large number of women responded that they do not go to gram sabhas because they are either not welcome at the meetings or they think it is not necessary for them to attend. They should also have greater participation in all spheres like participatory planning through voicin their concerns in gram sabhas, social audits etc.

Enhancing the Competitiveness of the MSME Sector through Cluster Development

The need of the hour is a cluster based approach. Clusters

are defined as a sectoral and geographical concentration of micro, small and

medium enterprises with inter-connected production system leading to firm/unit

level specialisation and developing local suppliers of material inputs and human

resources. Availability of the local market, intermediaries for the produce of

the cluster is also a general characteristics of the cluster.

As a whole, cluster facilitates to face market challenges, quicker dissemination

of information, sharing of knowledge and best practices and better cost

effectiveness due to distribution of common costs. It also provides an effective

and dynamic path for inducing competitiveness by ensuring inter-firm cooperation

through networking and trust. The geographic proximity of the enterprises with

similarity of products, interventions can be made for a large number of units

that leads to higher gains at a lower cost, which in turn helps in their

sustainability. The cluster approach thus aims at a holistic development

covering areas like infrastructure, common facility, testing, technology & skill

upgradation, marketing, export promotion. The Cluster Development approach has

played an important role in enhancing the competitiveness of the MSE sector.

Apart from the benefits of deployment of resources and economy of scales, the

cluster development approach helps in weaving the fabric of networking,

cooperation and togetherness in the industry, and thus enabling the industry to

achieve competitiveness in the long run. Cluster Development Approach is the

answer of the Micro and Small Enterprises to the large scale sector of the

country and the world and should be part of the business strategy. The Micro and

Small units are generally not in a position to install costly machinery for

their critical operations, accept large orders, or infuse large capital due to

their limited capital base and limited domain expertise. However, collectively

through cluster development approach, the micro and small enterprises can attain

the desired goal of being competitive in the present global scenario. The

Ministry has adopted cluster development approach as a key strategy for

development of micro and small enterprises in various clusters. The Ministry is

administering two cluster development programmes, namely, Micro and Small

Enterprises - Custer Development Programme (MSE-CDP) and Scheme for Upgradation

of Rural and Traditional Industries (SFURTI).

The objectives of the scheme is to support the sustainability and growth of MSEs by addressing common issues such as improvement of technology, skills and quality, market access, access to capital, etc.; to build capacity of MSEs for common supportive action through formation of self help groups, consortia, upgradation of associations, etc., and to create and upgrade infrastructural facilities in the new and existing industrial clusters of MSEs.

The cluster development initiatives in various clusters have reportedly delivered remarkable results. The guidelines of the MSE Cluster Development Programme (MSE-CDP) have been comprehensively prepared to provide higher support to the MSMEs. With this, more than 500 clusters spread over across the country have so far been taken up for diagnostic study, soft interventions and setting up of CFCs under the programme. The efforts under the scheme are focused on covering more and more clusters across the country. The Khadi and Village Industries, Handlooms, Handicrafts and Coir present a significant potential to generate rural employment. This paper briefly highlights Government’s initiatives to develop this sector and suggests enabling measures to generate significant employment.

District Rural Industries Project

NABARD launched District Rural Industries Project in 1993-94 in five potential districts to generate sustainable employment opportunities through rural industries. As on March 2009project covered 106 districts establishing 34,17,000 units and employing over 43,29,000 persons.