(Online Course) Pub Ad for IAS Mains: Union Government and Administration: Central Secretariat (Paper -2)

(Online Course) Public Administration for IAS Mains Exams

Topic: Union Government and Administration: Central Secretariat

The Secretariat has evolved over a period of 200 years. The Constitution does not mention the word ‘Secretariat.’ Article 77 (3) lays down that the President shall make rules for the more convenient transaction of the business of the government of India and for the allocation among Ministers of the said business. To run the business of the government the Secretariat is required. The word “Secretariat” has been derived from the word ‘Secret’, meaning, something held back or withdrawn from public knowledge or view, unrevealed, covert or confidential. The main function of the Secretariat is to advise the Minister in matters of policy and administration. The affairs of the State and particularly the dealings between the Secretary and the Minister are confidential in nature, therefore, the functions of the Government appears to have become synonymous with secrecy. Thus, probably for this reason the term, ‘Secretariat’ is derived from the world ‘Secret’.

During British rule in India the Government was the Secretary’s Government. After independence the real powers belong to the Council of Ministers. The Ministers obviously cannot work all alone and need assistance, therefore, for administrative purposes, the government of India is divided into ministries and departments which together constitute the “Central Secretariat”. Thus, the term central Secretariat is used to denote the sum total of the Secretariat staff of all the Departments/Ministries.

To implement the policies made by the ministers in consultation with the Secretariat there are attached offices, subordinate offices and other field agencies.

The Constitution also provides hosts of agencies independent of ministries/departments and report directly to the Union Parliament. Such agencies are, the Election Commission, the Union Public Service Commission and the Comptroller and Auditor-General.

In addition to these, there exists staff agencies to advise the government in the field of Planning but to practice it has become a parallel secretariat. Some Ministers and departments share their functions with boards and Commissions with some autonomy. Sometimes Ministries or departments have their own advisory bodies to assist and advice on specific matters.

Evolution of the Central Secretariat

The Secretariat in India in the beginning was the office of the Governor-General. The original role of the Secretariat was described as, “the Central Secretariat at Fort William in Bengal was designed to furnish the requisite information for the formulation of policy and to carry out the orders of the Company’s Government. Further B.B. Mtshra said, “before the year 1756 the President and the Council at Fort William transacted all their business in one general department with the help of a Secretary and a few assistants. On the arrival of packets from England the Secretary laid them before the Council for orders and instructions which when issued, were conveyed for execution to the priorities concerned.”

The Regulatory Act of 1773 for the first time created the ‘Supreme Government’, having controlling authority over the ‘Presidency Government’. It-consisted of a Governor-General and four councillors in whom all the powers of controlling and military of India vested. This system continued throughout the British rule. Only the number of members of the Council has been increasing. With the expansion of Company’s rule, it took a number of governmental functions and role of Secretariat expanded along with its size.

Lord Cornwallis took some steps to organise and strengthen

the Secretariat. He created the office of the Secretary-General in whom all

powers and responsibilities concentrated. He later came to be known as Chief

Secretary. Lord Wellesley also took a keen interest in re-organising the

Secretariat, and his reform works in the Secretariat increased considerably in

bulk and responsibility both. He raised the status of the Secretary to

Government. He did this by raising their salaries and augmenting their

responsibilities. The functions of Secretaries were extended to research and

planning in addition to their ordinary routine business of execution.

At the end of 18th century, the Supreme Government consisted of a Governor

General and three Counsellors, and a Secretariat of four departments. Each of

them was under a Secretary all of whom worked under the overall control of the

Chief Secretary.

After more than a hundred years on the eve of the Montford Reforms in 1919, the Government of India consisted of a Governor-General and seven members. The Secretariat also expanded and it had nine departments excluding the Railway Board and the Indian Munitions Board. The total strength of the Secretariat was 29 to which could be added 17 more officers of the two boards. This number remained unchanged till the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939.

The Montague-Chelmsford Reforms of 1919 brought about a significant change in the system of administration. The reforms introduced division of functions between the Centre and the Provincial governments and over a large part of the field, the provinces became virtually autonomous. Only subjects like the Army, Post and telegraph and Railways. were directly administered by the Central Government leaving the rest to the Provincial governments with the division of powers the Central Government came to administer many more areas directly. In consequence, the role of the Secretariat began to change from a merely policy formulating, supervising and coordinating agency to that of an executive agency as well. The trend got further impetus by the introduction of Provincial Autonomy in 1937 and later by the outbreak of the Second World War. Almost over night the Central Government was called upon to perform functions like Civil defence, mobilisation of men and material for was, food and civil supplies. As a result the post of officer on Special Duty was created in the Department of Home Affairs to look after the Civil Defence work. Later a separate department of Civil Defence was created and the Secretary of the department was also made the Director-General of Civil Defence. To look after many other areas, a lot of expansion in the Secretariat took place.

The strength of the Governor General’s Council increased from 7 to 14 and the number of Secretariat departments rose to 19. The total strength of officials also increased upto 200, under the belief, that the expansion was a temporary war time phenomenon and would be restored to its old position once normalcy was restored with the end of the war.

But, The, post-war-reconstruction programmes and later the advent of independence did not permit any reduction in the size of the Secretariat. On the other side post-independence problems and expanding social welfare functions of the new popular government further expanded the Secretariat. Thus, the number of departments in the Secretariat rose from 19 in 1945 to 74 in 1994; likewise number of attached and subordinate offices also increased from 20 in 1947 to near about 100 in 1991.

Functions of the Secretariat

The functioning of the Secretariat in our country has, by and large been based on two principles. First, the principle of separation of policy from its implementation-the administration in action, so that the latter can be handed over to a separate agency which enjoys certain freedom in the field of execution. Second, a transitory cadre of officers drawn from States Cadres, operating on the tenure system of staff controlling a permanent staff is a pre-requisite to the vitality of the administrative system as a whole. L.S. Amary in his book. ‘Thoughts on the Constitution’ pointed out that in such a situation of dual functioning. it is the policy making functions which are likely to suffer most. Routine business is always more urgent and calls for less intellectual efforts than the policy making functions. As the human mind tends to follow the path of least resistance. the routine functions got attended to, while the policy and planning questions are deferred. Therefore. it is only by the creation of a separate policy department general staff, freed from the administration as a whole that it is possible to secure for thoughtful and effective planning. This system is known as split system.

Advantages of Split System

Many advantages have been claimed in favour of the Indian system of separation of functions. The important ones are, first, freedom from day to day problems of execution provides opportunity to the policy makers to do the necessary for forward planning. Second, the Secretariat acts as the dispassionate adviser to the Minister. It has no interest in any proposal. The proposals coming from the executive agencies are examined in an objective way from the larger point of view of the Government as a whole. That is why the Secretary in the Secretariat is the Secretary not to his Minister, but to the Government on the whole. Third, the separation keeps the Secretariat’s size smaller. Fourth, this system also avoids over-centralisation. The executive agencies have to be given reasonable amount of freedom in the implementation of the policies and in the functions given to them. If the field functions were to be administered from the Secretariat it would have created lot of centralisation and delay in disposal of work.

The Present Status

There is no uniform terminology describing the various segments of the administrative structure of the Union government. In common terms, it can be said that the Central Secretariat is a collection of various ministries and departments. It is through this body that the Union government operates. It is the nodal agency for administering the Union subjects and establishing coordination among the various activities of the government. The functions of the Secretariat are as follows:

1. The Secretariat assists the ministers in the formulation of governmental policies. In this sphere, it performs the following functions:

(i) Making and modifying policies from time to time;

(ii) Drafting bills, rules and regulations;

(iii) Undertaking sectoral planning and programme formulation;

(iv) Budgeting, and controlling expenditure according to administrative and

financial approval of operational plans and programmes and their subsequent

modifications;

(v) Exercising supervision and control over the execution of policies and

programmes by field agencies and evaluating their performance.

(vi) Coordinating and interpreting policies; assisting other branches of the

government and maintaining contacts with state administration;

(vii) Initiating measures to develop greater organizational competence, and

(viii) Discharging their responsibilities towards the Parliament.

2. The Secretariat is a think-tank and virtual treasure-house of vital information which enables the government to examine its future policies and present activities in the light of past precedents. Nothing is lost to history and, time and again, it provides material for ready reference.

3. Before taking any action, the Secretariat carries out a comprehensive and detailed scrutiny of the issue, often taking the help of other ministries such as the Ministry of Law and the Ministry of Finance. An issue is thus discussed threadbare before it reaches the minister concerned.

4. In the Indian system, a rigid demarcation does not exist between the secretariat and field functions. The officers of the secretariat are transferred to the field and vice-versa. Thus, the Secretariat ensures that the field officers execute with efficiency and economy the policies and decisions of the government.

5. Lastly, it functions as the main channel of communication between the states or agencies such as the Planning Commission and the Finance Commission.

The Central Secretariat thus occupies an apex position. The ARC commented in this regard as follows:

"The Secretariat system of work has lent balance, consistency and continuity to the administration and serves as a nucleus for the total machinery of a ministry. It has facilitated inter-ministry coordination and accountability to Parliament at the ministerial level. As an institutionalized system, it is indispensable for the proper functioning of the government.”

Rules of Business

As already mentioned the Government of India is divided into a number of ministries/ departments for the purpose of efficient and convenient transaction of business. Article 77(3) of the Indian Constitution authorises the President to make rules for the convenient transaction of business of the Government of India and for the allocation among ministries of the said business. Two of these rules are:

1. The Government of India (Allocation of Business) Rules.

2. The Government of India (Transaction of Business) Rules.

These rules of business enable the minister or any other

official subordinate to him to exercise his power, subject to the responsibility

of the council of ministers to the Parliament. Under the Allocation of Business

Rules, framed under Article 77(3), a particular official of a ministry may be

asked to discharge a particular function. "When such authorized official does

any act, so authorized, he does so, not as a delegate of the Minister b-it on

behalf of the Government, subject to the overall control of the Minister and his

right to call for any file or to give directions, the validity of any decision

made by an authorized official cannot be challenged on the ground that the

decision was taken by an official and not the Minister concerned.” The

Transaction of Business Rules define the authority, responsibility and

obligations of each ministry in the matter of disposal of business allotted to

it.

A typical ministry of the Central government is a two-tier structure comprising

(1) the political head, that is the cabinet minister assisted by minister(s) of

state, deputy minister(s) and parliamentary secretary, if any; and (2) the

secretariat organization of the ministry with the secretary, who is a permanent

official, as the administrative head. Besides, there are executive organizations

under the heads of departments who function with the help of attached and

subordinate offices and field agencies.

Central Secretariat: Structure and Secretariat Officials

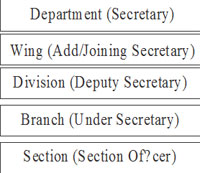

The Central Secretariat is a collection of various ministries and departments. A ministry is responsible for the formulation of the policy of government within its sphere of responsibility as well as for the execution and review of that policy. A ministry, for the purposes of internal organisation, is divided into the following sub-groups with an officer incharge of each of them:

Department : Secretary/Additional/Secretary/Special Secretary

Wing : Joint/Additional Secretary

Division : Deputy Secretary

Branch : Under Secretary

Section : Section Officer

In the larger Ministries, where the volume of work so requires, a recognisable area of work is entrusted to a separate department under the ‘charge of a-Secretary or Additional Secretary The business allocated to a Ministry/Department is generally divided into Wings, Divisions, Branches and Sections under the charge of a Joint Secretary, Deputy Secretary, Under Secretary and Section Officer respectively. Taking the posts of Director and Deputy Secretary as being at the same level, the structure of the Central Secretariat is composed of nine grades from Secretary/Special Secretary to Lower Division Clerk. While the minister is the political head of a ministry/department, the Secretary is the administrative head of the ministry/department. A single ministry may have several departments under It. For Instance, the work of the Ministry of Home Affairs is divided into five departments, including the Department of Internal Security, Department of States, Department of Official Language, Department of Home and Department of Jammu and Kashmir Affairs.

In case there are several departments within a ministry, each is headed by a Secretary/Additional Secretary/Special Secretary.

Department: Secretary: The Secretary is the administrative head of the department and the principal adviser to the minister. He represents his ministry/department before the Committees of Parliament. He is supposed to keep himself fully informed of the work of his ministry/department by demanding weekly summaries-on the nature of cases disposed of by lower levels and the manner of their disposal. Where the charge of a Secretary is too large, he may be assisted by a Joint/Additional Secretary who formall functions as Secretary in relation to the subject allot to him in the ministry/department. The function of the latter is to relieve the Secretary of a bloc of work and to deal, where necessary, direct with the minister. The Secretary, however, is invariably kept informed on all these direct dealings with the minister, for he is not formally relieved of his responsibility as head of the ministry/department.

Wing: Add. / Joint Secretary: Depending on the volume of work in a ministry/department, one or more wings can be set-up. An additional secretary/joint secretary may be made the incharge of a wing.

Division: Deputy Secretary: A wing of the ministry/department is then divided into divisions for the sake of efficient and expeditious disposal of business allotted to it. Ordinarily two branches constitute a division which is generally under the charge of a deputy secretary.

Branch: Under Secretary : A branch generally consists of two sections and is under the charge of an under secretary. The under secretary is also known as branch officer.

Section: Section Officer : The lowest of such units is the section-in-charge of a Section Officer and consists of a number of upper division and lower division clerks, dataries, typists and peons. It deals with the work relating to the subject allotted to it. It is also referred to as the office.

“Two sections constitute branch which under the charge of an under secretary, also known as Branch officer. Two branches ordinarily form a division which is normally headed by a deputy secretary. When the volume of work in a ministry/department exceeds the manageable charge of a secretary, one or more wings are established with ajoint secretary in charge of each wing. At the top of the hierarchy comes the department which is headed by the Secretary himself or in some cases by an additional/special secretary. In some cases, a department may be as autonomous as a ministry and equivalent to it in rank.”

The first three grades (Secretary/Add. Secretary/Joint Secretary) constitute what in administrative parlance may be called ‘Top Management’ while the grades of deputy secretary and under secretary, are referred to as the ‘Middle Management’.

The officer class, except the under secretary who is from the Central Secretariat Service Class I, is drawn from the IAS according to what is known as the tenure system.

The Secretaries are appointed out of a panel prepared for these posts. Rigorous screening takes place at the highest level, in which the Department of Personnel and Training, Cabinet Secretariat and the PMO are involved. The final approval to the panel is made by the Prime Minister himself. For the appointment to the individual ministries/departments, a secretary’s name for a particular department/ministry is approved by the Appointments Committee of the cabinet and finally assented to by the Prime Minister. The share of the IAS among the total posts of secretaries varies from time to time.

Tenure System

The system of filling senior posts in the Central Secretariat by officers who come from the States (or from the Central Services) for a particular period and who after serving their tenure, revert back to their parent States or services is known as the tenure system.

As applicable to the Central Secretariat, the tenure system dated from Lord Curzon time in 1905. It was reexamined in 1920 in view of the inquiry of Llewellyn Smith’s Committee which recommended that the tenure of the office of Secretaries and Deputy Secretaries should remain, although it should be extended from 3 to 4 years in order to give) a little more stability to the work of the Central Secretariat without affecting its living contact with the administration of the provinces. The Government of India, however, did not agree to the proposed extension. The existing tenure of 3 years was considered suitable by the Maxwell Committee (1937) in respect of Under Secretaries, though for Deputy Secretaries and Secretaries the period recommended was 4 years and 5 years respectively. The Wheeler Committee Report (1936) pointedly brought out the arguments in favour of the tenure system. It observed that as the hub of administration was at the district level, it was desirable that the members of the ‘steel frame (ICS) should have a firm grounding in district experience which would bring them into close contact with the people, train them to assume responsibilities and cultivate a sound judgment consequent upon handling a variety of problems.

Tenure system as such continued by the Government of India, even after Independence. The Study Team on Personnel Administration in its report 1967 gave its unqualified support for the tenure system and suggested the demolition of all barriers hindering an even flow of personnel between the Secretariat and the field. It made a positive recommendation that the tenure system be rigidly enforced and “officers must go back to the parent departments or State Governments as the case may be for a substantial length of time-not less than the period spent outside the department/State before being considered for another assignment.” The tenure for different positions at present are as follows:

Secretary : 5 years

Joint Secretary : 5 years

Deputy Secretary : 4 years

Under Secretary : 3 years

The reason for the continuance of the system may be summed up as follows:

1. A joint pool of officers at the reserve of both the Centre and the States

helps in administrative coordination at the Centre and State level and exercises

a unifying influence on the functioning of our federal polity.

2. The Central Secretariat benefits from the administrative experience of a

number of bureaucrats who have firsthand work experience at the district and

State levels.

3. A prolonged stay in the Secretariat may get senior bureaucrats out of touch

with actual administrative reality at the field level. The tenure system enables

them to get a constant feedback from the field and from the general public.

4. The States also benefit from having at their service experienced officers

with a wide national perspective on all problems.

5. Under the tenure system most officers are promised a chance of work at the

Secretariat thus equalising opportunities for all.

6. It strengthens the independence of the civil service. It is check against the

possible dangers of subservience by a few to the political masters for narrow

personal gains.

7. Lastly, the tenure system provided an easy way out to remove officers from

jobs for which they proved unsuitable and post them elsewhere.

Though the tenure system is still in operation, many arguments have been put forth against it. They may be summarised as below:

1. Bureaucratic work in the Secretariat is gradually becoming specialised.

The tenure system is essentially based on the myth of the superior efficiency of

the generalist civil servant.

2. District experience is really not necessary in many areas of Secretariat

work.

3. The tenure system has led to the bureaucrats getting too dependent on the

office establishment to get things done. This had led to “over

bureaucratization” of the Secretariat.

It is noteworthy that from its very inception the “tenure system” never governed all the posts under the government of India, the exceptions for the most part being found in the Foreign, Posts & Telegraphs, Customs and Income Tax Departments. The Wheeler Committee has given facts to prove that the complaint of the provinces that in a large number of instances they do not reap the benefit of the reversion of their officers lent to tenure posts is well-founded. Its analysis showed that (a) secretaries to the government of India either obtain higher posts or retire, they not revert to provincial secretariat, and (b) there is a distinct tendency to promote joint secretaries to be secretaries, deputy secretaries to be joint secretaries and under secretaries to be deputy secretaries and also for officers to hold on to successive secretarial posts in the same department.

The virtual break-down of the tenure system created a gap in

the manning of the senior secretariat positions. This led to the formation in

1938 of the Finance Commerce Pool of officers of the Indian Civil Service

another superior services like the Indian Audit and Account Service and the

Customs Service, who could devote themselves to, and specialize in, matters

covering finance and commerce. However, after 1946 recruitment to this pool was

discontinued. In 1957 after consultation with the State governments it was

decided to constitute a Central Administrative Pool as a reserve for manning

senior administrative posts of and above the rank of deputy secretary in the

Central government. The pool was to include officers drawn from the IAS, Class I

Officers of the Central Services including the Central Secretariat Service and

Class I Officers of State services.

The basic idea behind the scheme was to select persons and earmark them for

higher positions specially in the field of economic administration. The scheme

was duly approved by the government and even partially implemented when a storm

of protests from the States and from the IAS service associations led to its

suspension.The Central Secretariat Service is a major source of recruitment to

the Central Secretariat posts, it will be pertinent to discuss this service in

detail here.

Centra Secretariat Service (CSS)

Even before independence in 1947, the need of Secretariat Service was felt and the posts of assistant to that of Assistant Secretary /Under Secretary were filled by officers drawn from the Imperial Secretariat Service. After independence a scheme of such a service was approved by the Central Government in 1948 and was called the Central Secretariat Re-organisation and Reinforcement Scheme. It provided for a new service, called the Central Secretariat Service (CSS) to replace the old Imperial Secretariat Service. The new service was originally organised in four grades. But in 1959 as a result of the Second Pay Commission recommendation grades II and III were merged into one continuous class II grade. A new selection grade above Grade-I was also created which was to consist of the post of Deputy Secretary and above. The main features of the Central Secretariat Services are first, the service provides staff not only for the Central Secretariat but also for most of the attached and subordinate offices, and all posts from the level of assistants upto Under Secretaries are included in this service. Second, the new service was made a common service for all the ministries. This improved the opportunities and prospects of promotion for all the employees of the service. However, it was decided to introduce some element of decentralization in the service. The assistants and section officers are now divided into Ministry-wise cadres which means that the control over these levels now rests in the hands of the administrative Ministries concerned. But, for purpose of promotion to Grade-l the field of choice consists of all the officers in the section officers grade in all the cadres.

The control over Grade-l and selection posts now vests in the Department of personnel. Third, the Scheme visualised, from the very beginning. a deputation reserve in order to enable officers of the service to be appointed to the outside executive posts in attached and subordinate officers. This provision was made to widen the outlook and experience of the service and to strengthen the outside agencies. Finally, it was decided to establish a Secretariat Training School, to provide systematic pre-entry training to new entrants in grade III & IV of this service. Such a school was established in May 1948 and has now been upgraded to the status of the Institute of Secretariat Training and Management (ISTM).

Posts in the selection grade are filled by promotion on the basis of merit from officers of Grade I, having five years service in the grade. Recruitment to the vacancies in the grade of section officers is made in a number of ways. One-sixth of the posts are filled through UPSC on the results of I.A.S. examination. The remaining vacancies and also the temporary vacancies are filled by promotions of Assistants to the extent of 2/3rd of the vacancies and through a limited departmental examination conducted by the U.P.S.C. for the remaining one-third.

For the grade of assistants, the original scheme envisaged a reservation of 75 per cent of the permanent vacancies for being filled by direct recruitment on the basis of open competitive examination conducted by the U.P.S.C. However, to take care of the promotion opportunities of the Upper Division Clerks, the quota of direct recruitment has so far been kept at 50 per cent in place of 75 per cent. The qualification prescribed for direct recruitment is a university degree. The remaining 50 per cent vacancies are filled by promotion of meritorious upper division clerks of the Central Secretariat Clerical service.

Office Service

The office part of the Secretariat is manned by persons drawn from the two services, known as the Central Secretariat Stenographers Service and the Central Clerical Service.

Central Secretariat Stenographers Service

This service was reorganised on 1st August. 1969. It consists of four grades, such as Selection Grade, Grade-1 Grade-II, and Grade-III, The Third and Fourth pay commissions in 1986 have improved their service conditions.

Central Secretariat Clerical Service (CSCS)

This service has only two grades, namely, UDC and LDC. Recruitment to this service is at the level of ·LDC. 90 per cent posts are filled through an all-India Competitive Examination and the remaining 10 per cent vacancies are filled up by a limited departmental examination of Class-IV personnel who are matriculates and have more than five years of service. The examination for direct recruitment was also conducted by U.P.S.C. It is now conducted by the Institute of Secretariat Training and. Management under the department of personnel. The vacancies in the grade of UDC are filled by promotion from LDCs subject to the rejection of the unfit.

Criticism of the Secretariat

The need of the secretariat has not been questioned by its critics rather they favour the Secretariat to provide the necessary assistance to the Minister in policy making. Its working methods in actual practice have been criticised on many grounds. The points, of criticism are: First, the Secretariat is a: policy making body, but, it has started taking a number of field functions also. This is not good for administrative efficiency. In such a situation either the Secretariat does not get time to concentrate on policy making or the power and authority of field’ agencies is weakened. Second, the Secretariat tends to indulge in empire building. The various ministries and departments tend to undertake functions which are unrelated to their activity and this often leads to unnecessary expenditure. Third, the Secretariat has become an overgrown institution and over staffing is clearly Visible. To justify overstaffing the Secretariat tends to engage in unnecessary work. Fourth, the Secretariat personnel consider’ themselves superior to the field agencies personnel, even a junior secretariat officer’s behaviour with a senior field officer has not been good. They try to boss over them while their job is to provide them the necessary support by getting the policy framed for the performance of their field duties. The tenure system was devised for exchange of Secretariat and field officers for policies based on field experiences but in practice this purpose is not being served because now officers continue in Secretariat for too long. Fifth, the Secretariat has rules and procedures to be followed and the result is delay in decisions. The other reasons for delayed decisions are:

(a) the, lack of adequate delegation to the field units;

(b) cumbersome procedures and unnecessary number of levels through which it has

to pass before decision making

(c) the lack of feeling of responsibility and excessive dependence of higher

officials on their subordinates;

(d) over consultation unnecessary meetings interference from the top frequent

transfers etc. also cause delay.

Sixth, the tendency to have best officers in the Secretariat resulted field agencies starvation of good officers. Finally, coordination ‘has now become a real problem due to the proliferation of the departments in the Secretariat. The process of consultations among different Ministries/Departments take lot of time. They act as separate empires and do not take an overall view of the problems involved.

The above points of criticism depict the realities of shortcomings in the Secretariat. To overcome these weaknesses it would be desirable not to involve more than two levels below the authority involved in taking decisions. To avoid delay and cumbersome procedure sufficient powers should be delegated at the appropriate level. The ARC, in its report on the Machinery of the Government of India, has made some recommendation, in this regard, which are given below:

(A) (i) Non-Secretariat Organisations engaged primarily in planning, implementation, coordination and review of single development programmes or several allied programmes, covering a substantial area of the activities of the Ministry and having a direct bearing on policy making should be integrated with the Secretariat of the concerned Ministry, Such amalgamation is especially significant in the case of activities of scientific and technical character and activities which call for a high degree of functional specialisation.

(ii) The heads of Non-Secretariat Organisations which are integrated with the Secretariat should function as the principal advisers to the Government in their respective areas and should enjoy a status appropriate to the nature of their duties and responsibilities. They may retain their present designations. It is not necessary to confer on them a formal ex-officio status.

(iii) In all other cases, the present distinction between policy-making and executive organisations may be continued. Such distinction is vital for protecting the operational autonomy of the regulatory executive agencies and such developmental executive organisations as are mostly engaged in promotional activities, provision of a service or production and supply of a commodity.

(iv) Executive functions at present performed by an administrative Ministry or Department which do not have a close bearing on policy-making should be transferred to an appropriate, existing Secretariat agency or to a new executive organisation specially created for the purpose, provided that the volume of the work justifies its creation.

(v) Policy personnel in Departments and Ministries dealing

with scientific and technical matters or with functions of a highly specialised

character should include persons having relevant specialised experience or

expertise.

B. (i) In non-staff Ministries, other than those with the board type of top

management, there should be a set-up of three “staff’ offices, namely ; (a) an

office of planning and policy ; (b) a chief personnel office ; and (c) a finance

office. An Administrative Department with a heavy charge or with functions which

have no close affinity with the work of other Departments’ may have a separate

planning and policy office.

(ii) The office of planning and policy should include the planning cell recommended in the A.R.C, record of machinery for planning. This office should be continuously engaged in formulating long term policies, carrying out policy studies and evolving a series of well-articulated policy statements. It should also deal with the Parliamentary work of the Department/Ministry.

(iii) The Chief Personnel Office in a Ministry should serve as a focal point for the formulation and coordination of the overall personnel policies, initiating measures for promoting personnel development and service rules of cadres administered by the Ministry. It may also look after office management, O&M and general administration.

(iv) Each of the staff offices should be manned by staff having specialised knowledge and experience. The head of each “staff’ office should generally be of the rank of a joint Secretary though in some cases he may even be a Deputy Secretary or an Additional Secretary, depending, on the quantum of work.

(v) In addition to the three staff offices, each Ministry should have a public relation office or unit.

(vi) The head of the “substantive work” wings may deal directly with the Chiefs of the three “staff’ offices, as also with the Secretary and Minister on matters of technical or operational policy. Proposals having a bearing on long term policy should, however, be processed through the Planning and Policy Office.

C. (i) Distribution of work between the Wings of a Ministry / Administrative Department and within the Divisions of a Secretariat wing should be based on considerations of rationality, manageability of charge arid unity of command.

(ii) Each Secretariat Wing should have its separate identity and the budget should appear as a distinct unit in the budget of the Ministry. Its head should enjoy adequate administrative and financial powers.

(iii) The head of the Wing should have the Primary responsibility for good administration within the Wing effective supervision and control of staff and maintenance of high standards of disciplined conduct.

(iv) The head of the Wing should have considerable say in the formulation of the Wing budget creation of posts, subject to budget provisions spending of budget funds and appointments of personnel to the wing and’ their transfer there from. He should also have the necessary powers for effective day-to-day personnel management in the Wing. e.g., powers to sponsor staff for training, to grant honorarium, to impose minor penalties and to fill short-term leave vacancies.

D. (i) (a) There should be only two levels of consideration below the Minister, namely, Under-Secretary/Deputy Secretary and Joint Secretary/Additional Secretary/Secretary Work should be assigned to each of these two levels on’ the line of the desk officer’s system. Each level should be required and empowered to dispose off a substantial amount of work on its own and should be given the necessary staff assistance. (b) The staffing pattern within a Wing may be flexible to facilitate the employment of officers of various grades. (c) The duties and requirements of various jobs in the Secretariat at each of the two levels should be defined clearly in detail on the basis of scientific analysis of work content.

(ii) For smooth and effective working of the proposed “Desk Officer” system the following measures will be necessary:

(a) introduction of a functional system of the file Index;

(b) maintenance of guard files or card indices which will contain all important

precedents;

(c) adequate provision for “leave” reserve ; and

(d) adequate stenographic and clerical help.

(iii) (a) There should be set up in each Ministry or major administrative Department. a Policy Advisory Committee to consider all important issues of long term policy and to inject thinking inputs from different areas of specialisation into problem solving. The Committee should be headed by the Secretary of the Ministry and should include’ the heads of the three staff offices (of planning and policy, finance and personnel) and heads of important substantive work wings (including those of the Non-Secretariat· Organisation integrated with the Ministry / Administrative Department). As and when necessary the head of governing bodies of important research and training institutions and boards and corporations outside the Government may be coopted as members of the Policy Advisory Committee for such items of work as are of interest to them.

(b) Self contained papers or memoranda, setting out problems, their various alternative solutions, merits and demerits of each alternative, etc., should be prepared for consideration by the Committee and the, decision arrived at should be duly recorded in the ministry.

Desk Officer Concept

A major pieces of organisational restructuring was the enunciation of the Desk Officer concept. The attempt here was to convert the Central Secretariat into an officer-oriented system.

The Desk Officer system was introduced in January, 1973 in selected wings of Ministries where at least 40% of the work related to strategic policy making, planning and problem solving. Each desk comprised two officers of the rank of Under Secretary or Section Officer or both. The Section Officer submitted cases directly to the Deputy Secretary, while the Under Secretary submitted his fifes direct to the Joint Secretary. The idea was to abolish the Section, which has too much of supporting staff in the shape of assistants, UDCs, LDCs, Dataries, Peons, etc. The aim was to reduce the number of levels by at least two, to reduce the accent on noting and to lay stress on oral discussion, to foster greater participation in and commitment to organisational goals among officers at the base of the Secretariat structure. Each desk was given a well-defined area of functioning. SOs appointed as Desk Officers were allowed to authenticate orders and sanctions In the name of the President and to dispose cases on their own responsibility.

Currently, there are 1,816 Sections and 427 Desks government of India. The Desk Officer system has not made much head to the following reasons:

(a) Section Officers appointed as Desk Officers got all the

responsibility but without much monetary incentive. They were allowed a special

pay of Rs. 150 p.m., which proved insufficient to ‘motivate them.

(b) The staff unions saw the Desk Officer system as an attempt to reduce the

dependence of the Secretariat on the supporting staff like assistants, UDCs,

LDCs, etc. whose numbers are very large. They asserted their position in the JCM

and forced the Government to slow down the implementation of the new system.

(c) There was just one desk attaché or P. A. attached to the desk, with the

result that no memory could be built up, as in the case of the section. The

working of a desk got disrupted even by the proceeding of one of its members on

leave.