The Gist of Science Reporter: September 2015

Our Soil Our Future

“Soils don’t have a voice, and there are only a few people to

speak out for them. They are our silent ally in food production ... /r This was

Jose Graziano da Silva, Director-General of the Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAa) speaking on the occasion of the launching ceremony of the

International Year of Soils 2015.

The soils are in danger because of expanding cities,

deforestation, unsustainable land use and management practices, pollution,

overgrazing and climate change. The current rate of soil degradation threatens

the capacity to meet the needs of the future generations. The main goal of the

International Year of Soils is, therefore, to raise awareness about the

importance of healthy soils and to advocate for sustainable soil management in

order to protect this precious natural resource.

But, it is so sad and alarming that one-third of the soils

all over the world have already been degraded. If the current trend continues,

the global amount of arable and productive land per person in 2050 will be a

quarter of what it was in 1960. The world will have over 9 billion people in

2050, 2 billion more than today. Accordingly, the food production will have to

grow by 60% to feed this increased population, demanding intensive agriculture.

The pressure on soils is bound to increase and soils are not

easy to fix once they degrade: it can take up to one thousand years to form one

centimetre of topsoil. That same topsoil can be quickly washed away by erosion.

Soils are typically made up of about one-third water, one-third minerals and

one-third organic materials. But, if we take these three elements separately and

mix them together, we won’t get soil. Soil is much like a living organism. It is

a complex and dynamic system that forms habitat for an immense diversity of

species, including human beings.

It is composed of living and non-living components. The

living component includes from large creatures like earthworms, ants, etc. to

microscopic forms like bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and micro-arthropods. The

physical and chemical properties of the soil are attributed to the non-living

components of the soil. This largely includes the geological part, the solid

material, which we often call the ‘soil’.

The na ture of the soil varies across different geological

landscapes, their formation in turn affected by different climatic, physical and

chemical factors. Fertile soil remains as the base for the economic prosperity

of a nation through food, fuel and fabrics. Soil could even sustain

civilizations. It supplies nutrients for growth of plants which include

agricultural crops also.

Soils act as reservoirs of carbon and harbour dead bodies of

organisms like animals, plants and microorganisms. Soils can influence the

cycling of nutrients and energy in the ecosystems. Soil also plays a major part

in the Nitrogen and Sulphur cycles. In a forest land, the soil is always covered

by leaf litter composed of dead leaves, twigs and roots of plants. There is a

detritus food-chain going on within the soil, where the dead organic matter is

decayed by certain micro-organisms in the soil. During decomposition, the

organic matter is transformed into inorganic material such as compounds of

nitrate, ammonium, and phosphate which supply nutrients for plant growth.

For soils, quality is of prime importance. It means its

ability to maintain biological diversity and productivity. In the broader sense,

it is the ability to sustain quality of water and air and providing conditions

for plants, animals and human populations to live. Organic matter present in the

soil als determines its quality. A higher content of soil organic matter denotes

its higher cation exchange capacity, higher water-holding capacity and higher

infiltration capacity. When a soil naturally possesses better aeration and

increased soil particle aggregation, it can lessen soil erosion due to reduced

runoff of nutrients and improved moisture infiltration and retention.

Erosion is an inevitable action which implies the removal of the surface of the

earth by abrasive actions of wind, water, waves, or glaciers. Based on the

reason and factors, erosion can be of two types: Geological and Accelerated.

Geologic erosion is a slow process, typically occurring at a

rate that is much slower than the rate of soil formation. This rate would depend

on protection offered by vegetation. The roots of plants can intertwine with

each other and hold the soil particles together. The vegetation over-ground such

as grasses and certain other plants, which have even gained the name

‘sand-binders’, can protect the soil from washing away while the trees can

reduce the wind speed so that the loose soil is not flown away.

The opposite happens in the case of accelerated soil erosion.

Here the rate of soil loss is fas ter than the ra te of soil formation. When

there is a violent influx of wind or water, the individual particles of the soil

become detached from the aggregates and are washed away or blown away for great

distances. They are deposited somewhere else as dust or form new soils that are

washed into streams, rivers, and oceans. The extent of accelerated soil erosion

depends on natural conditions like climate, slope, vegetation cover, soil and

the nature of land exploitation patterns.

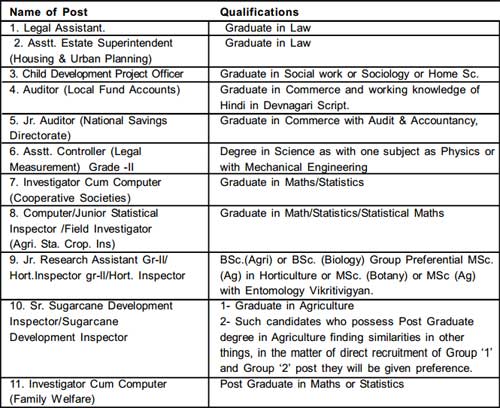

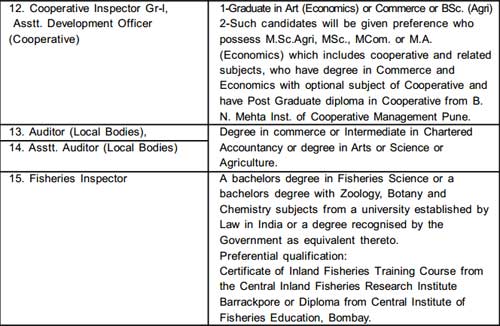

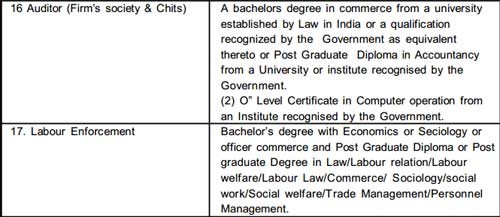

The

Union Minister of State (Independent Charge) Development of North-Eastern Region

(DoNER), MoS PMO, Personnel, Public Grievances, Pensions, Atomic Energy and

Space, Dr. Jitendra Singh disclosed that as a follow-up to the decision taken by

the government in the month of May this year, an expert committee consisting of

leading academicians, technocrats and senior bureaucrats of national repute has

been constituted to revisit the entire pattern, syllabus and eligibility

criteria for IAS / Civil Services examination. He was speaking to a group of

civil services aspirants, here today.

The

Union Minister of State (Independent Charge) Development of North-Eastern Region

(DoNER), MoS PMO, Personnel, Public Grievances, Pensions, Atomic Energy and

Space, Dr. Jitendra Singh disclosed that as a follow-up to the decision taken by

the government in the month of May this year, an expert committee consisting of

leading academicians, technocrats and senior bureaucrats of national repute has

been constituted to revisit the entire pattern, syllabus and eligibility

criteria for IAS / Civil Services examination. He was speaking to a group of

civil services aspirants, here today.